The Magical Properties of a Good List: Opening up Edward Gorey’s Notebooks

In the Fall of 2019 the Edward Gorey Charitable Trust allowed the House to borrow several boxes of Gorey’s notebooks, journals, folders, and binders of material for use in this year’s exhibit. In pouring over the contents (a nice way to spend a winter) of what would become our 2020 exhibit He wrote it all down Zealously, it quickly became apparent that the List was a defining component. A curator’s lament: the amount of material was overwhelming—and the handwriting challenging—and so the final assembly, whittled down to fit in the House’s galleries, was selected for variety and some semblance of narrative flow. A lot of very fine Lists that might have been displayed lost out to other very fine Lists getting displayed. In the culling I had to forgo lists involving house renovations, books about string art (a few snuck in), needlepoint schematics, Dr Who and Star Trek episodes, British monarchs, etching plates, vaccination records, mysterious columns of numbers—a lot of minutia that might have rounded out Gorey’s character will all have to wait until some future exhibit.

As you may have observed in last year’s exhibit, Hippy Wippity, The List was a common component of Nonsense Literature. The List offers a seemingly innocent bit of marginalia that tricks you into entering a juxtaposing wormhole. Edward Gorey, while always uncategorizable, can safely be labeled a Surrealist, a Nonsense Author and—a Listmaker. In fact, we’ve subtitled this year’s exhibit Edward Gorey’s Interesting Lists because the List is such a defining element throughout the notebooks. Lists were just one of the many things that Gorey obsessed over—and he wasn’t all that unusual in doing so. For many people, the List is an indispensable organizing ritual. It prioritizes tasks visually in a way that gives the impression that order has triumphed over chaos—it allows some hyper people to sleep at night. Also, taken out of context, a list (especially someone else’s list) is a wonderful document, both a peek into one’s internal machinery and often—and not least—a poem. Indeed, because of their delightful randomness, many of Gorey’s lists are wonderful literary objects in themselves, some are vastly more enjoyable than his actual poems.

Gorey filled specific notebooks with lists of films he had viewed (he called these 20 small spiral notebooks The Diary of a Lost Boy—discussed below). He listed films yet to be seen, and books to be read. Gorey left selective lists of some of the 26,000 books he owned—citing mostly mysteries, and not creating a comprehensive catalog (that’s still being done at the San Diego State University Library). There are notebooks listing his music collections (mostly Baroque, but with generous portions of Gluck, Satie, Gregorian Chants, ragtime, and, somewhat inexplicably, the complete works of Tom T. Hall). Notably absent is any written record of the thousands of performances by the New York City Ballet which Gorey attended between 1953 and 1983. Instead, Gorey retained the ticket stub to each performance (if it was choreographed by George Balanchine)—as if each experience transcended the written word, and a small color pasteboard keepsake would have to represent each experience.

Gorey’s music lists allow us to see the mundane mechanics of someone who enjoyed purchasing and (we assume) listening to music. His music notebooks are comprised of 2159 albums (as of 1979—lists after that are currently missing or still buried in archival debris). Keeping up with evolving technology, Gorey purchases his first CD (Fourth Book of Madrigals by Monteverdi) in August of 1990, and in October, 1999, lists his 4,666th and final noted CD purchase (Overtures by Berlioz). While we have the list of when Gorey recorded Star Trek: The Next Generation (We’ll Always Have Paris episode) on VHS (May 7th, 1988) we unfortunately do not know when he actually viewed it. This hole in our knowledge is actually something that keeps the brows of Gorey Scholars furrowed.

The Diaries of a Lost Boy (Volumes I to XVII)

Edward Gorey at the Movies

Gorey’s longest list involves film. Gorey had an unquenchable thirst for watching movies—all movies, but specifically silent films (“Movies made a terrible mistake when they started to talk,” he once stated). His film viewing history—entitled The Diary of a Lost Boy—fills the 17 small pocket notebooks shown here. The existing lists start in 1957, though Gorey notes that several earlier journals were lost (possibly eaten by cats), so he recreated some partial lists from memory. In addition to first run films logged, Gorey noted films seen at the Elgin, the New Yorker, and the Thalia art film houses in New York, as well as at the MOMA’s Saturday morning film series. A large number of the films listed are through the Theodore Huff Memorial Film Society—Huff in the journals. Using constantly rotating venues, the Huff was presided over by William K. Emerson, an independent film publicist and collector, who conducted all-night movie marathons of silent and foreign films in his apartment, noted in the journals as Bill’s Apt. As an interesting addendum to the 1000-plus films Gorey claimed to view a year, he also recorded the days when he did not see any films.

Gorey’s nearly-nightly film viewing was neither a distraction, nor wasted time (though it is confounding where he found the time). With a vast library of melodramatic structures and archetypes filed away in his head, the visual and storytelling techniques of silent film became a major influence on Gorey’s own evolving style. His characters may have been Edwardian, but his design sensibilities and sparse narrative style were swiped unaltered from the tableaus of early silent films (this in itself the subject of a future blog).

“Serving no purpose and having no point”

The List as a thing in and of itself

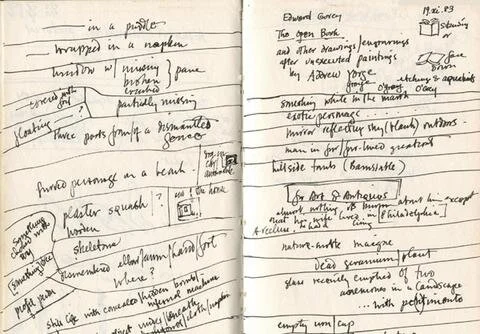

Above all else, Gorey’s Lists reveal the vast number of works he had under consideration. Even if progressing no further than a title, they provide a partial glimpse into his internal universe of what-ifs. Several unfinished titles from this time involve a boy named Piermont, the successor to Donald (they look identical actually) in the books that Gorey illustrated for Peter Neumeyer. Piermont lists include The Piermont Quartet Counting Book, The Piermont Quartet Picture Book, and The Piermont Quartet Alphabet Book among others. Piermont, and his dog Miss Amanda Bones, also play a prominent role in The Interesting List a book which Gorey proposes obliquely to Peter Neumeyer as a possible collaboration in an October 1968 letter:

“Donald Makes a List. Donald makes careful Donald-like preparations: cleans his pen, receives several sheets of beautiful thick paper from his mother, plants both feet firmly under his chair, and writes out a list—all sorts of wild, poetic, baroque things, not necessarily objects, with each item a drawing, and the list (serves) no purpose (and has) no point except its own existence. When it is finished in Donald’s best calligraphy, he puts it away in a drawer, and goes off to the kitchen where his mother gives him an apricot turnover and a glass of milk. End.”

(Floating Worlds Pg. 45).

Edward Gorey and Peter Neumeyer would publish three books together between 1968 and 1970. Unfortunately The Interesting List would not be one of them. This year’s exhibit features what exists (or what has currently been unearthed) of The Interesting List in fragments of finished art, sketches, and outlines. Whether The Interesting List might have become a surrealist masterwork along the lines of The Object Lesson—we’ll never know for sure. It does reveal Gorey’s attachment to the List as a thing in and of itself to be celebrated, and as a vehicle into much broader and much deeper associations.